Beginning work on a vocabulary

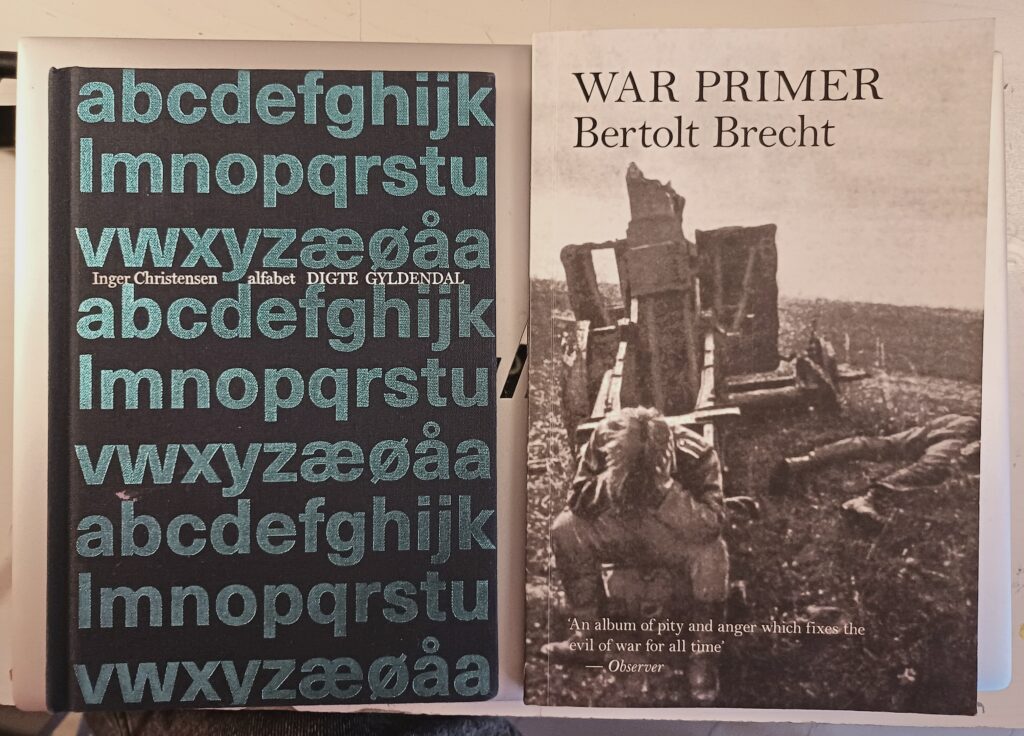

While I am on Gotland, visiting all the peace activists that I can find, two books of poetry accompany me. One of them is alfabet, by the Danish poet Inger Christensen. The other one is War Primer, by Bertolt Brecht, compiled partially while he lived in exile in Sweden. I look to the work of Inger Christensen for its formal qualities as much as for the subject matter. Her long-form poem is a list of things which exist in the world: many of them elements of nature like flowers and animals and weather phenomena; some of them man-made; and a few of them man-made weapons of both small-scale and mass destruction. That these few items on the list, like the hydrogen bomb, possess the power to eradicate all the other things, all the elements of nature, is chilling, frightening, vertiginous. The poem speaks with a quiet sadness, but it also uses insistence, insistence upon bearing witness to life.

When I visit a nature preserve on Fårö, on the northernmost end of Gotland, I find myself standing on a stretch of coastline which has no visible signs of life: the rock under my feet is black and looks as if it had melted once during extreme heat and then solidified again, like a stream of lava reaching the ocean. The waves have worn the edges off everything. There is nothing growing on this rock, no moss or algae, and there are no birds in the sky at this moment. I wonder if there is any life in the waters before me. What I see is only dead black rock, grey ocean, and grey sky, and I think that this is what a world without any life to witness it would look like. It would still be beautiful, a wonder of creation, but there would be no one to witness it, to appreciate it, to be filled with wonder at the beauty of it.

When I visit the far south of Gotland a few days later, when I’ve gone in the opposite direction, I meet with a priest who has founded a Peace Center. He talks of the necessity of dialogue with the people of Russia. I mostly talk of how a destroyed world would be a world without witnesses, I am still taken by that stretch of coastline up north. Taken by a landscape that says to me, that it is peaceful, but only because it has no life.

In War Primer, Bertolt Brecht has combined photographs cut from newspapers with short poems, or epigrams. Each page has one image, and a poem to comment upon the image. A primer is a book of ABC’s meant for teaching children to read, or, a short introductory text on a subject. Brecht wrote his War Primer during and shortly after the second world war, as an introduction to the forces which give us war. He had planned to follow it with a Peace Primer, but that plan never came to fruition. I imagine I could use the idea of this never-written Peace Primer, this ABC of peace or this short introductory book on peace, as inspiration for an artwork to come out of my stay on Gotland. This introduction to peace which only exists as an idea, in potentia. Never witnessed outside of the mind of a writer who is long dead.

On Gotland, I visit people every other day. In between, I write down what I recall of our talks. But I mainly look through the images which they have given me.

I meet an international diplomat who has negotiated in six wars. I meet a retired UN soldier who speaks of his struggles with putting words to experiences. I meet people who organised enormous peace marches in the early 1980’s, one beginning in the north of the island and one beginning in the south, eventually converging in the city of Visby, somewhere in the middle. These peace marches had support from the prime minister of Sweden, who vacationed on Gotland every summer, and who was approachable to his neighbours. I meet people who are arranging protests against the Swedish application to join NATO, struggling in the face of public discourse, facing condemnation – what a contrast to those people marching in the early 1980’s, with the wind in their backs. I meet with groups of environmentalists, draft dodgers, historians, volunteer workers.

Our talks are not planned beforehand, in the sense that they could have been interviews. They are much more free-form. I listen to their stories and their thoughts, their memories and their feelings, their analyses. I speak of whatever I come to associate with what they bring up, or I speak of something that I saw or heard the day before, at a previous meeting.

Maybe I lose the thread, sometimes during these talks. But the people I meet all show me images and press clippings and sometimes an object connected to a memory they have. The priest at the Peace Center in the south of Gotland shows me a short film, of how his emails to every member of the Swedish parliament are sent out one at a time by an automated program, with the names of every politician passing through the address field. He thinks I might find this little film clip interesting – and I do. It’s a new format, but the same struggle, to be heard. Will any of these politicians even open his emails? When I contrast it with images from a conference, held in a remote location (Folk och Försvar, at Högfjällshotellet in Sälen January 7th-9th, 2024), where lobbyists of the weapons industry have unrestricted access to Swedish politicians and military leaders, I am again struck by the difficulties that peace workers face. The Swedish Prime Minister makes a public statement from the conference, claiming: one, that Sweden must prepare for a coming war; two, that immigrants or descendants from recent immigrants should be viewed as cowards and traitors to the country, because they do not wish to defend it. His statement is debunked many times over in the following weeks, but the impact that he, and by extension the lobbyists of weapons manufacturers, have on public discourse is far wider than a steady voice reasoning for diplomacy and dialogue.

The people I meet all show me images, as I said. They are images which I could include in a future artwork, whatever that would turn out to be. Maybe a Peace Primer, with images rather than poems commenting upon other images. Maybe images that turn up in all these meetings on Gotland could be placed in contrasting pairs, as if on a double spread in a book, and together communicate a thought or a feeling which is not formulated into words.

The images I am presented with are either documentation of an organised event, i.e. potential historical documents, or images with a double nature. Most of them do not present an easy statement but rather speak of the complexities of working with a peace project. Some people have prepared before our meetings, dug up old scrapbooks and photo albums. Others come to think of some image as we sit talking, by an association which has just formed, and bring them out while I wait.