ONLY HERE COULD BERGMAN AND TARKOVSKY HAVE MADE THEIR FILMS…

Performing the ghost in Gotland

written by Danae Theodoridou

‘Excuse me, but where is Gotland?’ I hear myself asking with a slight embarrassment in one of the first meetings of the On Mobilisation cohort, when I learn that I will visit it and act as a ghost there for the visual artist Kalle Brolin.

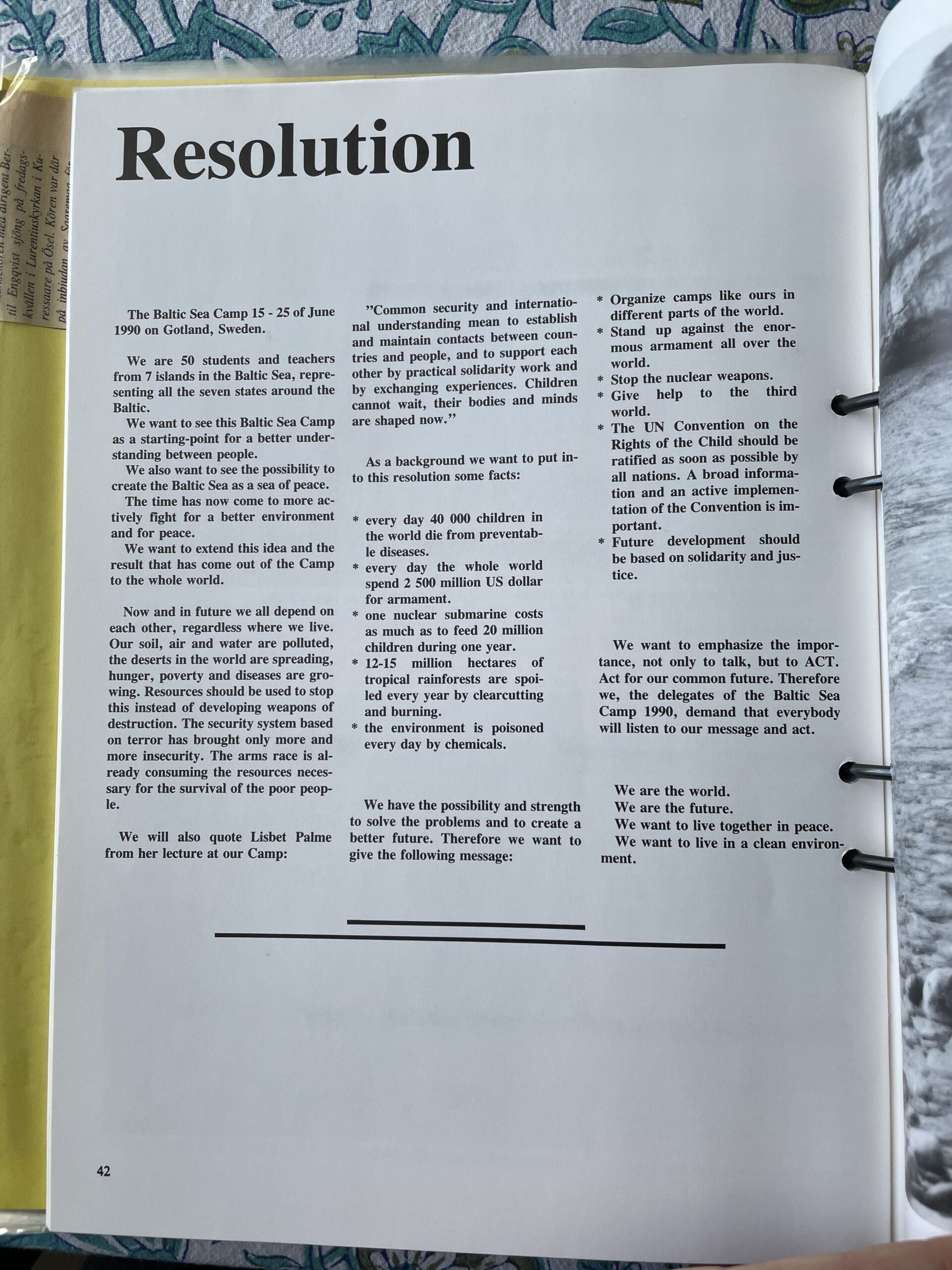

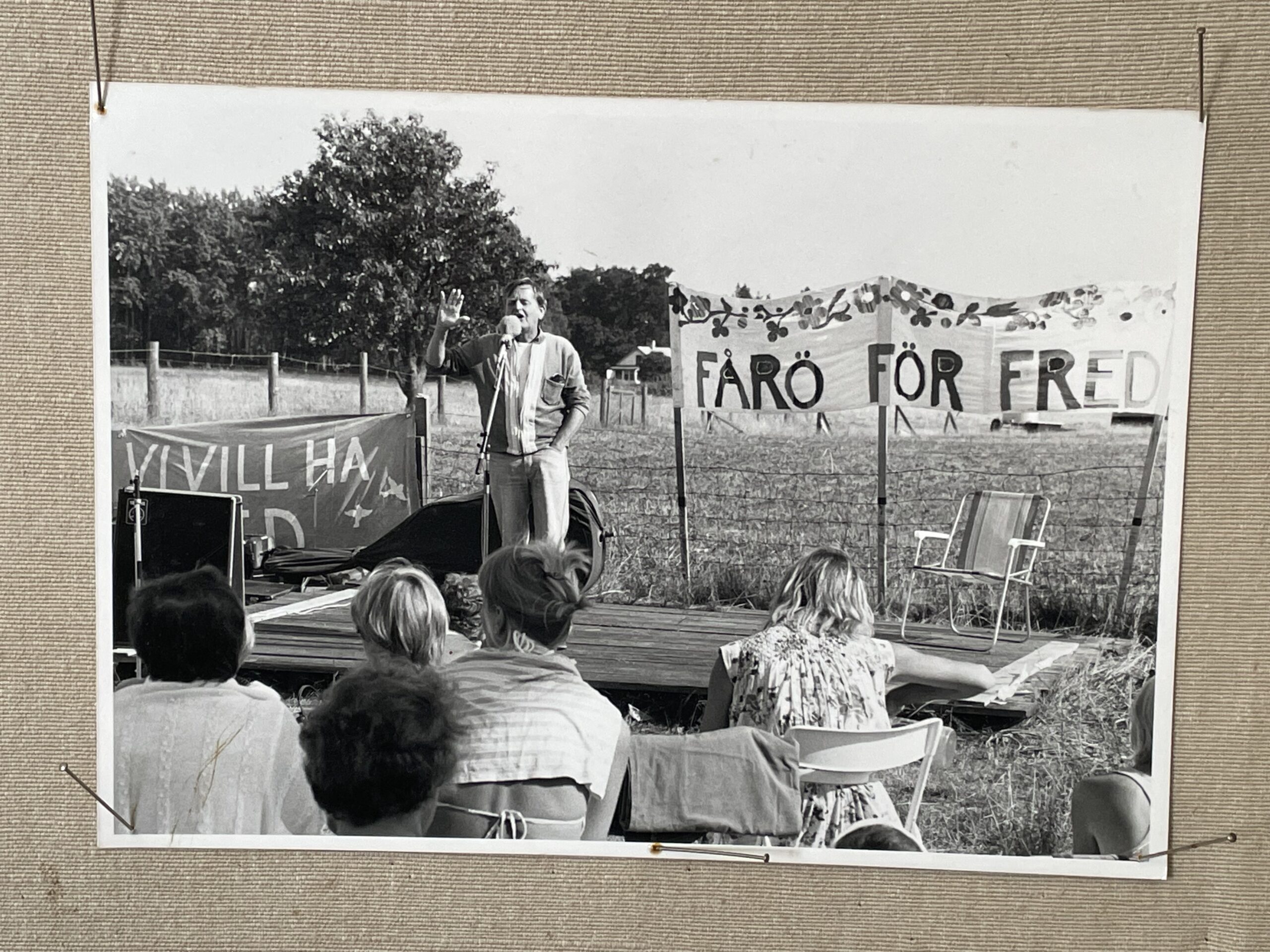

What paired Kalle and me, I learn, is the common focus of our work on language and the creation of citizens’ vocabularies related to social movement. Kalle would meet people from various peace movements in Gotland (active mainly in the 1970s and 80s but also today), which raise their voice against the extended (national and international) military presence in Gotland. ‘What kind of language can stand next to such institutionalisation of war?’ was Kalle’s main question in this case. His aim was to work on the (impossible?) task to (re)mobilise the peace movement of Gotland and create together with its people a new vocabulary, a particular form of alphabet for peace and solidarity.

For the last five years, I work extensively on a larger project of artistic research that I call The Practice of Democracy. In its frame, I create a series of score-based participatory encounters where inhabitants of different cities in Europe meet to explore and practice together different democratic practices (such as public speaking, assembling, protesting a.o.). The scores I create – namely, a series of instructions for thinking, speaking, moving – are mostly language based. In my case, the question is: what kind of language can mobilise people to experiment more imaginatively with politics and come up with alternative (to capitalism) ways for practicing social coexistence.

The connection between Kalle’s and my work seems then clear enough; what was left to discover was what exactly I would have to do as his ‘ghost’ in Gotland. How could I stand next to a person working? Especially when this work includes close one-on-one encounters with people who – moreover – speak Swedish, a language that I don’t speak? As what could I – a foreigner – stand between Kalle and his interlocutors? Suddenly, the idea of the ghost started to look more attractive. Being there but so discreetly that I could even pass unnoticed…

Among recurring talks with Kalle, scheduled visits to churches, art museums, local galleries and the architectural remains of Gotland’s military history:

…what followed included also a series of unique, unexpected moments:

– for the first time in my life, I drive a boat assisting Kalle in his search for an old assembly space, now hidden under the waters of a lake

– an activist whose place we visit, tells me that I am sitting exactly on the same spot of her couch, where one of the main political figures of the Greek socialist party -who she knew personally- had seated. The visit suddenly takes an unforeseen historical turn (especially when thinking the current political situation of my homeland characterized strongly by extreme rights voices) and involves me directly. Many ghosts in the same room… I am overwhelmed by the rich archive of texts and images she shared with us, as well as by her generous hospitality.

– During one of the short road trips we did with Kalle in Gotland and its surrounding islands in the frame of his planned visits, I find myself daydreaming while looking outside the window. Such a generous treatment of space, I catch myself thinking. Everything here looks exceptionally spacious, such long fields, so sparsely populated areas; an open space that opens also space for the mind and heart to wander. Later, I learn that Andrei Tarkovsky has filmed his Sacrifice here, whereas Ingmar Bergman has made many of his films in the small island of Fårö, which is almost attached to Gotland. It makes absolute sense. The rare open, spacious temporality that is so characteristic of their work could only have taken place here.

– In another road trip of ours, I am surprised to hear Kalle asking: ‘Now, apart from accompanying me, what is there for you and your work here? What can I do for you?’ In such generous shift of focus, a ghost can materialise itself in mysterious ways. It is after a couple of hours that my dream to visit Bergman’s house and his grave comes true.

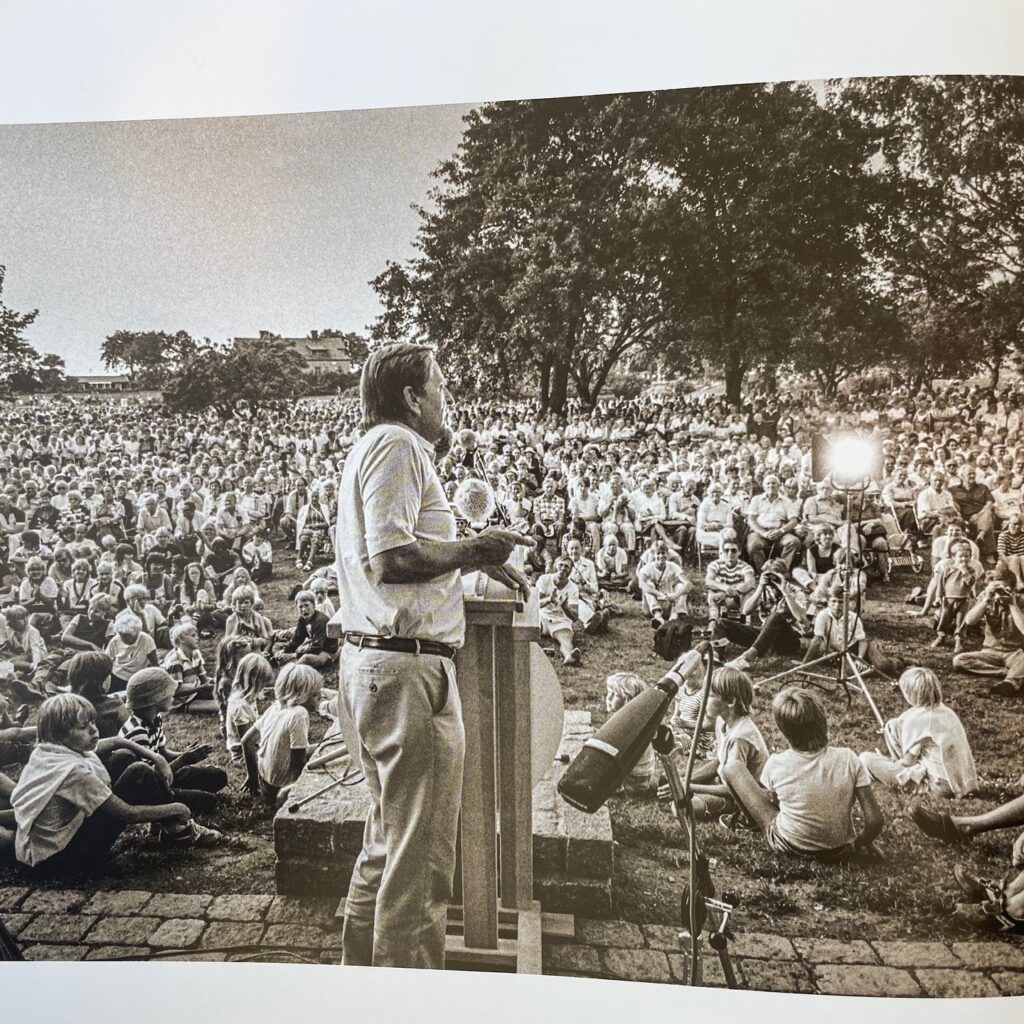

– It is also then that I learn about the Almedalen Week, a unique festival of democracy that emerged in 1968 -when Olof Palme, minister of education at the time, spoke from the back of a lorry at Kruttornet in Visby- and is taking place, since then, every year in Visby. During the last day of my ghost visit in Gotland, I spend time visiting the park where Almedalen takes place and read about the event in the local library, which stands right opposite the park (such nice alignment of knowledge, language and political action). Suddenly Kalle’s question ‘what kind of language can stand next to such institutionalisation of war?’ seems to get a good reply here…

…later in that day, I hear that in the last decades, Almedalen has taken a tricky twist, becoming mostly a lobbying event for Swedish political parties, a kind of prestigious party for the press, which impacts severely the local community in terms of infrastructure, prices that are ridiculously high during that week etc. Palme would definitely be sad to see the frustrating collapse of democracy in these last decades…

Towards the end of my ghosting week and as the rest of the On Mobilisation cohort arrives in Gotland for our meeting, I find myself grounded strongly back to my main questions of interest, through an inspiring detour, though, which gives a new light to them: how can art contribute to the reactivation of truly democratic practices today and become a strong alternative to the toxic rhetoric of war, violence and hatred that is so popular today? How can art offer a frame, through its language and structures, for ‘demos’ -namely the people- to empower themselves and claim back their power as the first, constitutive part of demo-cracy?

During our cohort meeting, I am asked to reflect back at my experience as a ghost and share some thoughts on it. I write and share the following with the group:

“It starts with a suspicion (what is this forced collaboration about?) and a certain guilt (how can someone – in this case Kalle – do his work while at the same time having someone else -in this case me – asking questions, time, attention?). How could I intervene in another’s working process? How to not become an annoying burden?

It then evolves into an existential question: what is my role here? What am I supposed to do? What does a ‘ghost’ normally do?

And it ends (at least from the side of the ghost) as a triple act of:

-

- resistance: the ghost as a great opportunity to slow down, ‘waste time’, against the continuously accelerated working rhythm of capitalism that mainly executes things, often with only superficial results. When there is not much to do, other than following someone, time feels different and holds another type of potential…

- mutual generosity: as a ghost one learns, as Bojana Cvejic has argued, to ‘stand under’, i.e. support, before she ‘under-stands. During our days of exchange with Kalle, we both learned how/when to be there (for each other) and how/when to leave space and (dis)appear; how and when one should (not) be alone.

- emerging knowledge: when one does not (need to) ‘know’, when one has no expectations or nothing to prove (to the demanding art market), then things come only as rich, unexpected surprises of new insights, appearing from different directions in ways that one cannot (and should not) control. Maintaining such positioning towards knowledge is a core concern I have in my work and, at the same time, the greatest challenge we all face, I guess, as (art) workers in such harsh neoliberal contexts. Most of the times we fail but maybe the important thing is trying…”

In my recent book Publicing – Practising Democracy through Performance (Nissos 2022), I propose a careful approach to ‘locality’ as a core working principle for reactivating democracy via art. The practice of ghosting could be seen as the ideal practice to enter the ‘locality’ of a new place. Entering Gotland’s locality as a ghost has insightfully taught me, once more, the complexity, contradictions, paradoxes involved in internal political debates.

As I travel back home, the local flight from Visby to Stockholm is full of soldiers and other army officers who probably also travel back home for the weekend. I am thinking that for a week we were sharing the same place, that small piece of land, working in such different ways on how we can live together.

Next to such armed force, our protest slogans, our bodily language and actions evolve in time looking for ways to make poetry and political emancipation, mutual understanding and support, constitutive part of our democracies…